It’s been a while since I updated this blog, but I often find it helpful to process my thoughts about a subject through writing. So I’ve returned several years later to write about what I’m doing now - teaching high school Physics.

I’m teaching two different classes right now - one is a 9th grade integrated science course, where students take two trimesters of physics content and one trimester of chemistry. The other is AP Physics (I’m teaching both AP Physics 1 and AP Physics C: Mechanics, but now that they took E&M and Waves off the AP Physics 1 exam, it’s basically the same curriculum). I’m trying to focus on being project-based, incorporating lots of hands-on labs (which students have been craving in quarantine), and teaching students professional skills like reading research papers, scientific writing, and thorough documentation of their work.

Right now I’m struggling with an open-ended circuitry project for my 9th graders. These are the instructions I gave them. I just want them to start playing around with circuits, but in an intentional way. I want them to design a circuit to accomplish a particular goal, then build towards that goal. It prevents them from taking the easy way out, building overly simple circuits, and not really learning much along the way. I also wanted to make sure that they weren’t building huge, bulky projects out of cardboard that would take up a ton of room in my classroom. So I had them focus on input and output. A user does something (turns a dial, flicks a switch), and something else happens (an actuator pokes something, a fan turns on, etc).

The interesting thing here is that the potentiometers and clickers I provided have three terminals - so students could build parallel circuits. And some of them did. So far in class, we’ve only talked about loop circuits, Ohm’s Law, and Kirchhoff’s Loop Law. This project will hopefully open the door to talking about parallel circuits in the coming weeks.

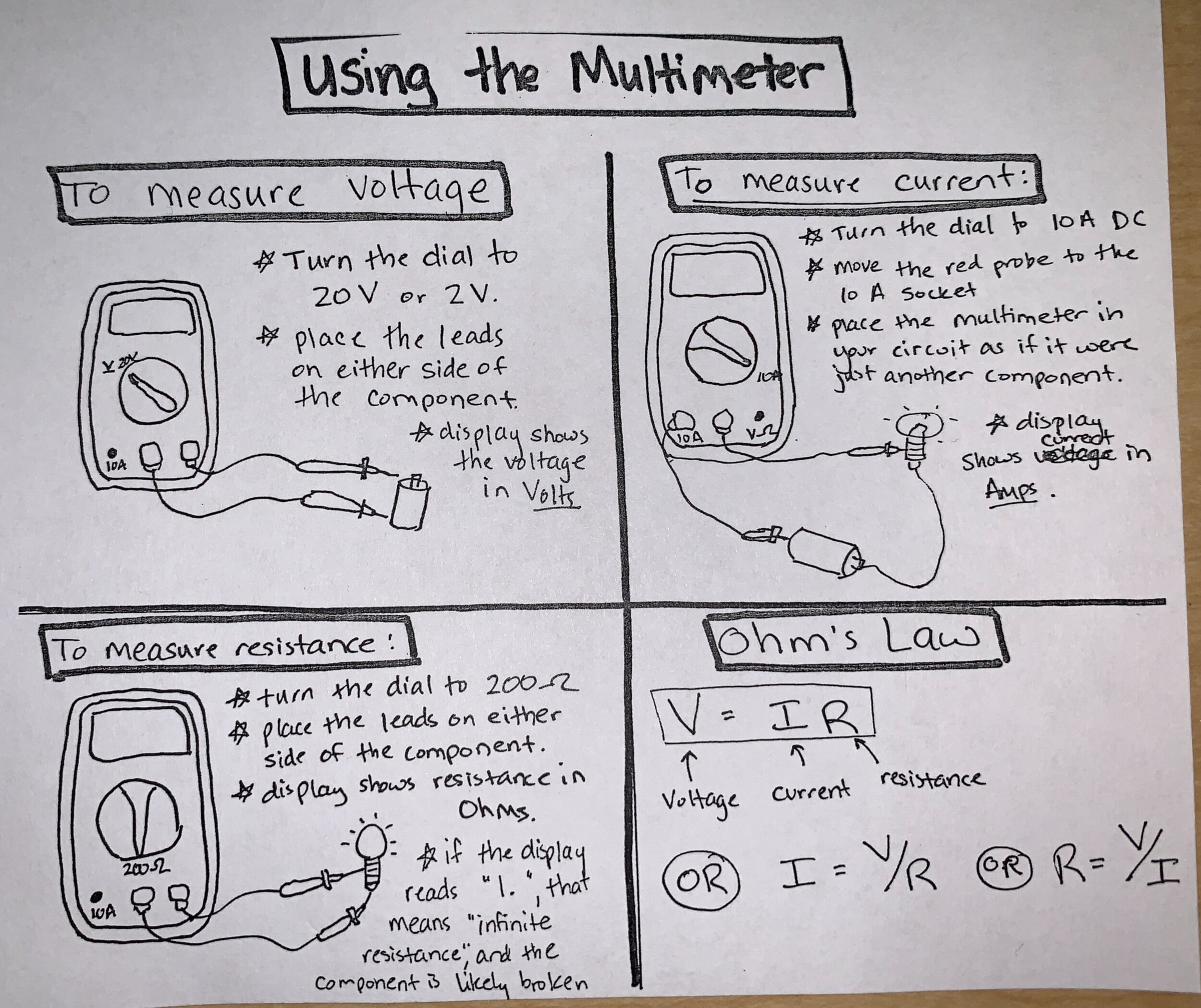

One major challenge I have is getting students to use the multimeters. I made a little cheat sheet and asked them to tape it into their notebooks, which tells them how to use the multimeter to measure voltage, current, and resistance, and provide’s a reminder about Ohm’s Law. But the amount of troubleshooting needed to get the multimeters working properly has been getting in the way of the learning. Burned out light bulbs, poorly attached motor terminals, half-dead batteries that aren’t providing enough voltage - these have been plaguing us. I don’t feel as though I have the time to teach them the sort of instincts needed to troubleshoot these sorts of issues, nor do I think it’s necessary for a lab where I just want them to learn about series and parallel circuits. But I also want them to face challenges that feel surmountable. I’m not sure I’ve reached the right balance yet, but I’m working on it.